Modern Architecture Ascends in Aspen

Inspired by the up-and-down movements of the skiers on Aspen Mountain, the Pritzker Architecture Prize laureate Shigeru Ban takes modern building design to dramatic heights with the new Aspen Art Museum.

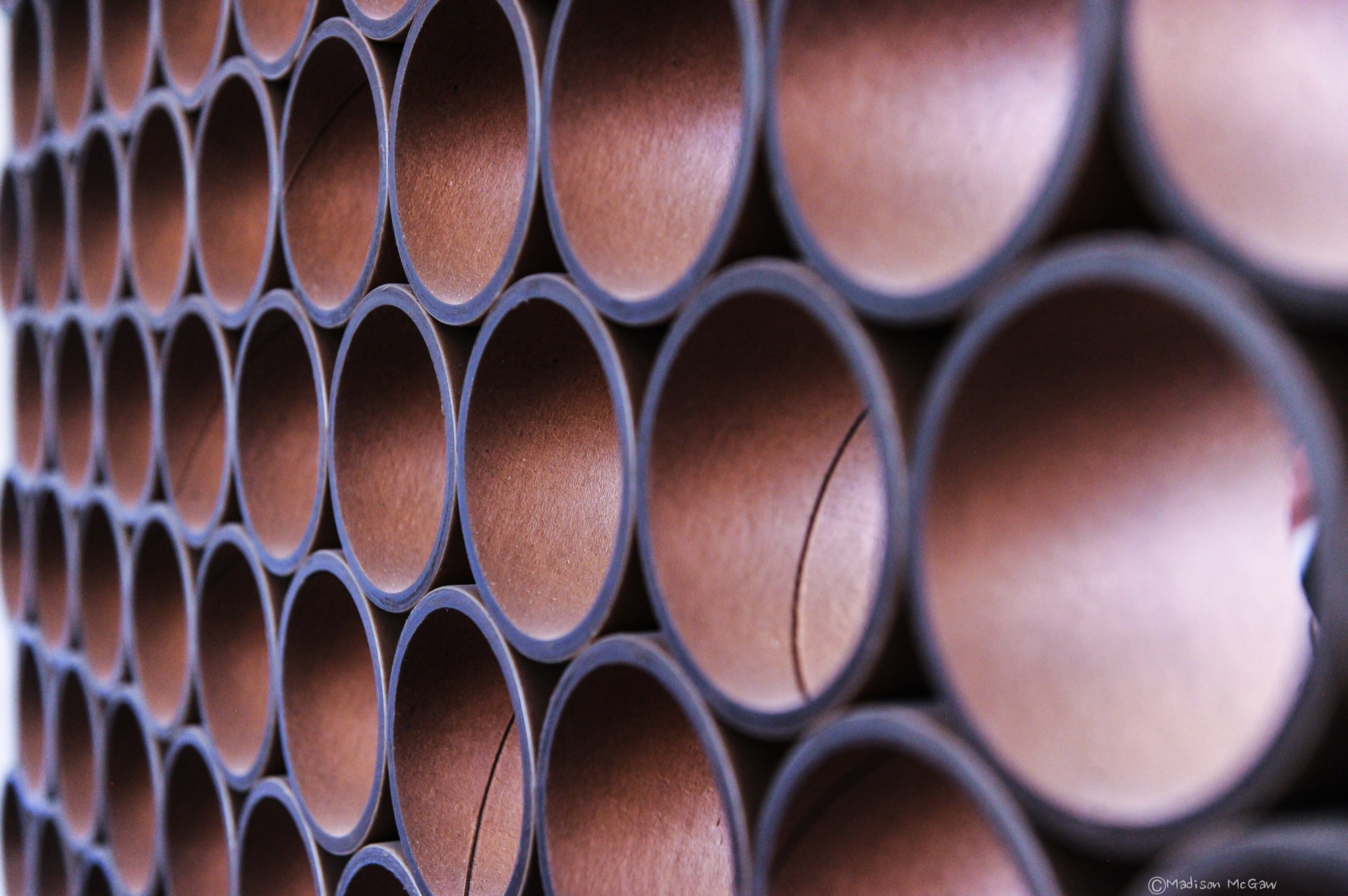

The new Aspen Art Museum, which opened in August 2014, became an instant, if controversial, landmark in the precious Colorado mountain town and beyond. Architect Shigeru Ban’s building is like no other in Aspen — or anywhere else. Think of it as a box within a box. The blocky three-story glass interior box is wrapped within an outer box made of wide strips of resin-impregnated paper woven into a grid, permitting light and air to filter in and people to look out. In daylight, the strips have a wood tone. The texture relates to old bricks, the dominant building material in downtown Aspen. The strong vertical and horizontal lines play off the glass in an ever-changing succession of light and dark, bright and shadow.

Up and down — like the skiers

Ban’s concept was to echo Aspen Mountain, the commanding presence just south of downtown. At the ski area, skiers ride lifts to the top and then make their way down. So it is at the museum. Visitors first ascend the stairs or ride a room-sized glass elevator to the only public rooftop space in Aspen, with its open sculpture garden, grand view of Aspen Mountain’s lower slope, and an indoor/outdoor café where visitors linger over a cup of coffee, a light bite, or lunch. The menu changes frequently, appropriate for a museum whose exhibitions change every few months. Then visitors work their way down. Six galleries, three above ground and three on the basement level, have already showcased the works by painters, sculptors, installationists, and multimedia artists. A show in Aspen has a way of increasing an artist’s visibility and renown.

Curating the new

The new building replaced the 7,500-square-foot (ca. 700-square-meter) former hydro-electric plant that had housed the museum since 1979. While it was of nostalgic value to the Aspen community, it had long since outlived its usefulness as a museum that showcases contemporary art and also hosts workshops, classes, music programs, lectures, and films. In this global art world, the call for design ideas was broad, but from concept to opening involved an eight-year process. Heidi Zuckerman, the museum’s visionary director, CEO, and chief curator, says that when it was time to choose an architect, the only two requirements provided to a selection consultant were that the architect had previously designed a museum and also spoke English.

Shigeru Ban came with both. As for museums, he had designed the Centre Pompidou-Metz, a regional branch of the famous Georges Pompidou Arts Centre of Paris. The Metz outlier contains exhibitions from Europe’s largest collection of twentieth- and twenty-first-century arts. He also did the Nomadic Museum to house “Ashes and Snow,” Gregory Colbert’s groundbreaking video/photo work, that launched in Venice, then traveled to New York, Santa Monica, Tokyo, and Mexico City, ending in 2008, largely due to the global recession. As for language, Tokyo-born Ban had studied at the Southern California Institute of Architecture and New York’s Cooper Union, and he now divides his time between Tokyo, New York, and also Paris.

The selection consultant had put out the call without revealing the specific client and came back with pictures submitted by thirty-six firms — “no names, no words, just pictures,” Zuckerman says. Sixteen firms were then told that the Aspen Art Museum was the client, and fourteen of those submitted plans. A committee narrowed those to five and visited three. “Shigeru came in with the highest score at every round,” Zuckerman continues. She was already familiar with Ban from his Paper Arch, erected in the courtyard of New York’s Museum of Modern Art as part of its millennium celebration.

"Shigeru came in with the highest score at every round."

Ban’s Backstory

Time magazine named Ban the 2001 Innovator of the Year for his pioneering disaster relief designs that used simple materials to build housing in afflicted areas. Ban is known for innovative and distinct designs, of course, but also for the humanitarian and sustainable aspects to his work. He has made his reputation on using simple materials, from paper and cardboard to crates and shipping containers, to help people, communities, and countries rebuild their lives after headline-making disasters.

Projects included using sandbag-filled beer crates as the foundation for quick-to-build, low-cost housing after the 1995 earthquake that devastated Kobe, Japan. Sixteen years later, following the massive quake and tsunami (think Fukushima Nuclear Plant) that left 300,000 people homeless, Ban designed homes crafted from shipping containers with cardboard tubing for interior walls. He expanded on this concept with his “cardboard cathedral” that rose from the rubble of the quake-damaged Catholic basilica in Christchurch, New Zealand. With cardboard tubing as the visible structural element, it stands as a symbol of hope and inspiration while the city contemplates whether or not to reconstruct the copper-domed classic. The cardboard tubing tradition lives modestly at the Aspen Art Museum in the form of benches.

For fifty-seven-year-old Shigeru Ban, 2014 was a landmark year. Even as his $45-million USD Aspen Art Museum was in the final stages of construction, he was awarded the prestigious Pritzker Architecture Prize, considered the most important honor in the field. It rocketed him to “starchitect” status and made the museum’s twenty-four-hour grand opening the place for well-heeled Aspenites and the art-world elite to see and be seen.

In presenting Ban with the coveted prize, Tom Pritzker, president of the sponsoring Hyatt Foundation, said: “He is an outstanding architect who, for twenty years, has been responding with creativity and high-quality design to extreme situations caused by devastating natural disasters. His buildings provide shelter, community centers, and spiritual places for those who have suffered tremendous loss and destruction.”

It may seem counterintuitive that an architect known for creating housing for refugees and disaster victims did his first U.S. building in one of the country’s priciest towns, and Zuckerman is clearly relieved that her museum snagged him pre-Pritzker. It makes sense, actually. Ban is disinterested in monumental buildings, and as one of only a handful of noncollecting museums in this country, the AAM did not require massive space. It is a mere 33,000 square feet (3,065 square meters), with three stories at and above street level and one below.

"Ban is disinterested in monumental buildings."

Not for everyone

The Aspen Art Museum is built to the sidewalk line, like the nearby late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century buildings, meaning that it is not out of scale with its neighbors. But the exterior materials and the see-through grid are what turned heads and shocked some locals. People love it, detest it, or are merely puzzled by it, but everyone knows it is an extraordinary community resource, especially since admission and many of its programs are free.

Zuckerman’s uncanny instinct for identifying the next hot new contemporary talent makes the Aspen Art Museum a coveted venue, even though each exhibition lasts only about three months. “I feel fortunate to have as a platform this incredible museum,” says Zuckerman, who, mindful of the controversy surrounding the design, adds, “It can be for anyone, even if it is not for everyone.” In its first six weeks, the new museum drew some 35,000 visitors — as many as the old museum did in a year.

“I feel fortunate to have as a platform this incredible museum. It can be for anyone, even if it is not for everyone."

Aspen and modernism

While it values its Victorian core, Aspen has had an ambivalent relationship with modern architecture. Eero Saarinen’s original music tent for the Aspen Music Festival was replaced twice, most recently by a permanent structure designed by Aspen’s Harry Teague, and the modest concrete Given Institute by Chicago modernist architect Harry Weese was demolished in 2011.

The pure Bauhaus-era Aspen Meadows Resort on the city’s east end remains a living icon with low-slung buildings designed by Austrian-American architect Herbert Bayer. It is the home of the Aspen Institute, a humanistic think tank for leaders, artists, musicians, and thinkers. It also operates as a hotel with spacious accommodations and a fine restaurant on a forty-acre campus. Sections of the ground have been sculpted into little hills, a gentle serpentine trench to replicate a watercourse and pebbled paths plus carefully selected rocks and sculptures placed here and there. With much change in the valley, Aspen Meadows is a keeper, and so is the Aspen Art Museum. △