Minimalist Pottery in the Kyoto Mountains

The Shinkansen bullet train from Tokyo to Kyoto departs not one minute late, travels almost 200 miles an hour, passes Mount Fuji on the way, and pulls into Kyoto’s vaulting modern station not one minute early. From there it’s 40 kilometers by car to Shigaraki, an industrial mountain town, where I’ve come to visit a ceramic artist whose work has transfixed me on Instagram for the past ten months.

Shigaraki is home to one of Japan’s “six old kilns.” The most admired pottery here—tea bowls and sake cups made from local iron-rich clay—is often misshapen and haphazardly glazed. Much is left to the felicitous violence of earth and fire in wood-fueled kilns. These clay items, used in the exquisitely calibrated tea ceremony, are prized for their imperfections, reflecting the wabi-sabi philosophy in which earthiness, transience, roughness and decay reveal the essential nature of the world.

Such is Japan: hyper-curated, thrillingly modern, clockwork precise—then offering you a tea bowl that seems primeval.

The ceramic artist I’ve come to see, however, is Tetsuya Otani, whose work departs so thoroughly from the Shigaraki style as to seem from another world. Otani’s hand-thrown porcelain chases the precision of machine manufacture. Its skin is smooth and naked, like that of a baby. I wanted to know why he was making such beautiful but plain stuff.

Right now, though, I have a few hours to kill, so I drive into the mountains to find the I.M. Pei-designed Miho Museum. The Miho is a kind of Japanese Getty, opened in 1997. It’s perched on a thick-forested mountain top like something a hermit might build if the hermit had several hundred million dollars. To reach it you walk through a hill via a gleaming, curving science-fiction-y pedestrian tunnel and emerge on a bridge that’s supported by a harp-string array of steel cables. The Miho was commissioned by an industrial-fortune heiress who also made time to found a sect in the 1970s, variously described as an art-centric religion and a sinister cult.

As traveler’s luck would have it, the museum is showing an astounding collection of ceramics by the 18th-century artist Ogata Kenzan, whose name means “northwest mountains.” His painted cups, bowls, and trays leave the viewer giddy, so varied and playful are they in style and form.

At home with Momoko and Tetsuya Otani

Five or so kilometers from the Miho is the home that Tetsuya Otani shares with his wife Momoko—also a gifted ceramic artist—and their three girls and a dog. It’s beautiful, with farmhouse mud walls and high wood beams that employ traditional temple joinery. Everything on the main floor revolves around the kitchen, which is far larger than usual in a Japanese house, reflecting the Otanis’ passion for communal cooking and eating with friends, many of whom also make pottery. The shelves, in the dining area and kitchen, are filled with both Tetsuya’s and Momoko’s pieces.

The work of Tetsuya Otani

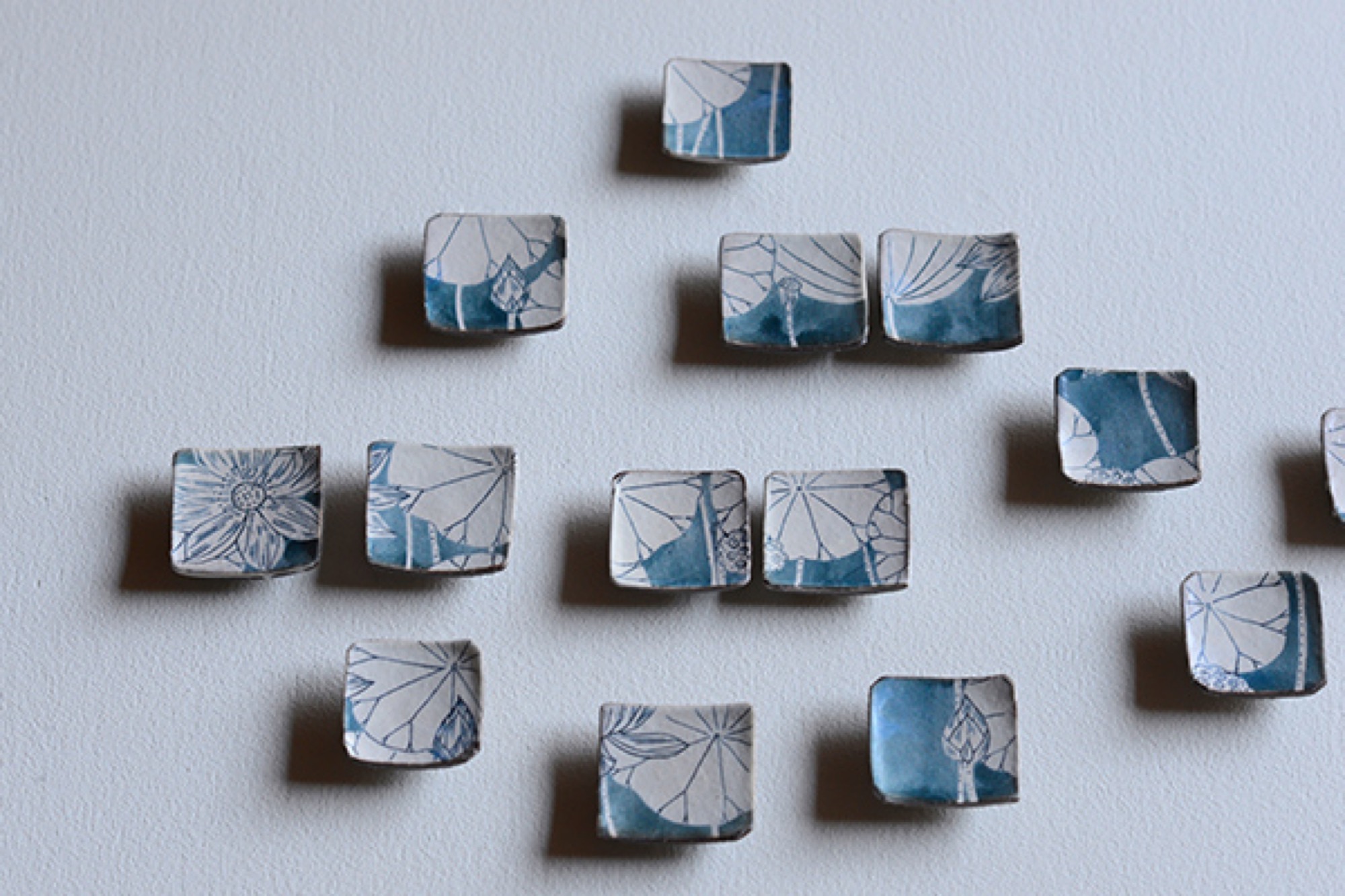

Lately attracting attention among collectors in Beijing, Shanghai, and Taiwan, Tetsuya shuns both wabi-sabi imperfection and Kenzan decorative exuberance. Everything he makes is to be used, mostly in the kitchen or at the table: tiny matcha urns with clinking lids, curved-belly flower vases, delicately spouted teapots, tiny soy dispensers, little round boxes. The pieces are finely lipped and polished to a supple smoothness; their creamy matte glaze begs to be caressed.

Tetsuya’s pottery has thrown off all temptation toward decoration. The potter’s goal, he says, is to remove as much information as possible from his ceramics, seeking pure functional forms, because “things that work give pleasure.”

"The potter’s goal, he says, is to remove as much information as possible from his ceramics, seeking pure functional forms, because 'things that work give pleasure.' ”

He studied in Kyoto, hoping to design cars, but when the economy skidded in the nineties, he shifted to graphics and ended up teaching product design (“how to make molds”) at the Ceramic Institute in Shigaraki, where he met Momoko and, on the side, learned throwing and glazing clay. By 2008, their house was built and he embarked on a ceramic career. He’s now in his late thirties.

I watch him work in the studio, which has wheels for him and Momoko, as he forms and pokes a bit of clay that will become a tiny strainer inside a teapot. A few feet away, a large machine mixes clay while sucking air from it, then extrudes large, irresistibly smooth noodles of the stuff. The machine is close to the same color as the clay. Tetsuya grins and admits he had it custom-painted to obliterate the standard industrial green. A clue to his fastidious brain.

The pure cup and the pure bowl

Later, we sit at the long kitchen table and look at bowls and cups and teapots and plates and discuss this idea of removing information from one’s work.

“The pure cup,” Tetsuya says, through Momoko’s translating, “and the pure bowl: They can accept anything, become a vessel for anything. Cultural information is eliminated. And then the cup or bowl can be applied to any culture.”

“The pure cup and the pure bowl: They can accept anything, become a vessel for anything. Cultural information is eliminated. And then the cup or bowl can be applied to any culture.”

One may begin with the form of a traditional Japanese offering bowl. Decorative motifs are removed until it approaches neutrality. Eventually you “come down to the point where we can use it on our table, not for the gods’ offerings.”

Momoko adds: “Tetsuya strips the bowl of the divine.” He produces smooth dinner plates as blank canvasses for food—altars, really. They’re used in fancy Osaka and Kyoto restaurants to showcase chef art. His works are unsigned, unmarked.

“Tetsuya strips the bowl of the divine.”

But cultural negation negates a specific culture, and Tetsuya says he has lately realized, when showing his works in China, that they are in some way indelibly, irreducibly Japanese. “I now feel that,” he says, “but I don’t have the answer yet about why I feel that way.”

The potter approaches, but never finds, ideal functionality. Tetsuya tweaks the ancient teacup form a wee bit from batch to batch, always seeking the right feel of cup in hand, the right curve of handle against thumb and finger. This lonely, incremental search for ideal form, endlessly repeated, is itself very Japanese.

The motivation is pleasure, however, not denial. Tetsuya and Momoko are exuberant foodies, and have found that their table-centric philosophy resonates globally through their gorgeous Instagram feeds, @otntty and @otnmmk, with more than 20,000 followers between the two for their pictures of utensils and food.

Tetsuya is also funny. He calls the clay mixing machine Mr. Hiroshira, “my only employee.” What about the beautiful industrial kiln in the next room, I ask? “No,” he says, “I work for it.”

Return to Kyoto

A few nights later, in Kyoto, my wife and I visit a little chocolatier and bakery called Assemblages Kakimoto, near the Imperial Palace. In the minimalist showroom up front I buy a box of orange biscuits enrobed in dark chocolate, each biscuit not much bigger than a postage stamp. Beyond the front space is a narrow, pretty room with a half-dozen seats or so against a counter, facing a tiny kitchen. We order chocolates and cakes and glasses of thirty-year-old palo cortado sherry. Two women to our right—the only other customers in the café—have come for the chef’s omakase dinner. With each course they look gobsmacked, enraptured by the treats placed in front of them. It’s beautiful food, for that is the Kyoto style. Each composition sits on the pale canvass of an Otani plate.

The entanglement of much fuss and no fuss that lies at the heart of many things Japanese is hard to describe, but when I palm one of the Otani pieces that we brought back from Japan, it seems to embody that contradiction. My favorite is a little round vase, the size of a tennis ball, whose satin smooth sides curve up to a sharp-lipped hole that’s big enough to accommodate the stem of a single bud. In weight and delicacy and touch and every other aspect the vase seems, to me, as close to perfect as it can get. It holds a lot of information about Japan. △